Zimmer's Second Return

By Aidan Monks

The tablets of the twenty-first century film score were carved by Hans Zimmer. Beginning his film career (after a brief stint as a keys player) in the underground British cinema of the 1980s, Zimmer broke into the industry with his avant-garde work on Barry Levinson’s Rain Man (1988) after being scouted for his music on the anti-apartheid drama A World Apart. As we have come to expect from Zimmer, the music for Rain Man is anything but derivative - rather than incorporating the ornamental slide guitar of the ‘road movie’ genre, Zimmer favoured synthesisers, steel drums as well as strings. As early as the late ‘80s, his sound exhibited an idiosyncratic fusion of electronic and orchestral elements.

You may ask: What about John Williams? Ennio Morricone? What about Howard Shore’s perfect work on The Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001-3)? True, true, and true. No matter how great a film composer is, there is little chance of them avoiding John Williams adjuncts and comparisons; when you have a composer who has underscored the childhoods of several living generations, their melodies become difficult to escape. The same can be said of Morricone (who composed for Sergio Leone, Guisseppe Tornatorre, Brian De Palma, and Quentin Tarantino) whose music above all else inspired Zimmer. (See Once Upon a Time in the West.) These old masters, few of whom are still alive, came to define film composition in the 1960s and 1970s having themselves been influenced by the musical talents of classical Hollywood - Alex North, Bernard Herman, Max Steiner, etc. Their music is scolded into the fabric of film grammar. However, of the generation that followed, evolving from the technological transformations of pop in the 1980s and the ascent of neoclassical minimalism (contrast: John Williams’ maximalist orchestrations) in the mainstream, Hans Zimmer has burgeoned into the most influential paradigm. We should consider Hans Zimmer with regards to this musical style, pioneered by heavyweight names like Philip Glass and Steve Reich, which purported to convey the same feelings and ideas with much ‘less’.

In 2007, Zimmer was named by the Daily Telegraph as one of the only living geniuses. By 2007 he had composed some of his most iconic scores - from True Romance to The Lion King to Gladiator to Pirates of the Caribbean - including the so-called “forbidden cue” for Terence Malick’s epic The Thin Red Line (‘Journey to the Line’), so dubbed for its frequent use as a temp track by editors to construct dramatic escalation. ‘Journey to the Line’ is a masterful slow-burner which critically introduced Zimmer’s iconic clock-ticking motif subsequently displayed in The Dark Knight, Inception, Interstellar, and Dunkirk, all of which released after his genius was heralded. To claim that his ‘greatest’ compositions were produced after 2007 would be, while certainly debatable, well-founded. Planet Earth II, Blade Runner: 2049, Kung Fu Panda, Sherlock Holmes, and 12 Years a Slave also fall into this post-genius category of Zimmer classics, all of which demonstrate his prodigious contribution to Hollywood cinema. By the time his score for Denis Villeneuve’s first Dune film was nominated for an Academy Award in 2022 (successfully) the world was reminded that, since his first win in 1995 for The Lion King, Hans Zimmer had not received mainstream awards acknowledgement for his work, despite his authoritative presence within the film industry. Cut to 2024: Zimmer is already in talks for a third Oscar for its sequel, anticipating the 97th Academy Awards by exactly twelve months.

Dune: Part Two was released in the United States on March 1, a week after Hans Zimmer’s latest masterpiece became available on all platforms. Two singles from the soundtrack - ‘A Quiet Time Between the Storms’ and ‘Harvester Attack’ - were released a few days prior to the album drop to generate interest, and provide the film with effective marketing. Hans Zimmer is a name which, at least in cineaste circles, draws attention to a movie like few others. Perhaps this is due to his close collaboration with Christopher Nolan (probably the most popular filmmaker of the new millennium); Zimmer’s scores for films like The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar were ultimately the scapegoats of otherwise second-rate blockbusters. However, what has been reaffirmed with his successes on the Dune franchise (which he elected to work on over Tenet and Oppenheimer) is that Zimmer’s brilliance exists outside of this iconic collaboration.

Frank Herbert’s Dune novels were some of Zimmer’s favourites as a young man, immersed in the cultural submersions, suppressions, and intersections of Arrakis as he moved from Germany to London with high hopes for a musical career. You can hear Zimmer’s passion for Herbert’s world(s) in his music as vividly as in John Schoenherr’s illustrations for the first novel. In the first Dune (2021), Zimmer utilised choirs (emphasis on female vocals) alongside heavy percussion in a sonic turn reminiscent of his work on The Thin Red Line and The Last Samurai. Similarly, these elements of Dune’s sound function alongside string instruments to fully entrench audiences in the cultures and climates of Herbert’s societies. There were less character melodies than thematic leitmotifs in the film, presenting the concept of journey, dreams, prophecy, or youth through specific instruments and tones. The differences between leitmotifs are at times extreme, and at other times harmonious. However, it is between extremities that Zimmer’s score achieved experimental subtleties and cultural distinguishment. Compare the otherworldly dreamscapes introduced in the film’s opening sequence to the ‘Bene Gesserit’ arrhythmic whispering manifesting, and containing, the secrets and lies of the Lisan al Gaib (Freman term meaning ‘messiah’). As soon as the soundtrack’s third song, Zimmer has convinced listeners of the complexities, diversities, and nuances of culture and history in the Dune diegesis.

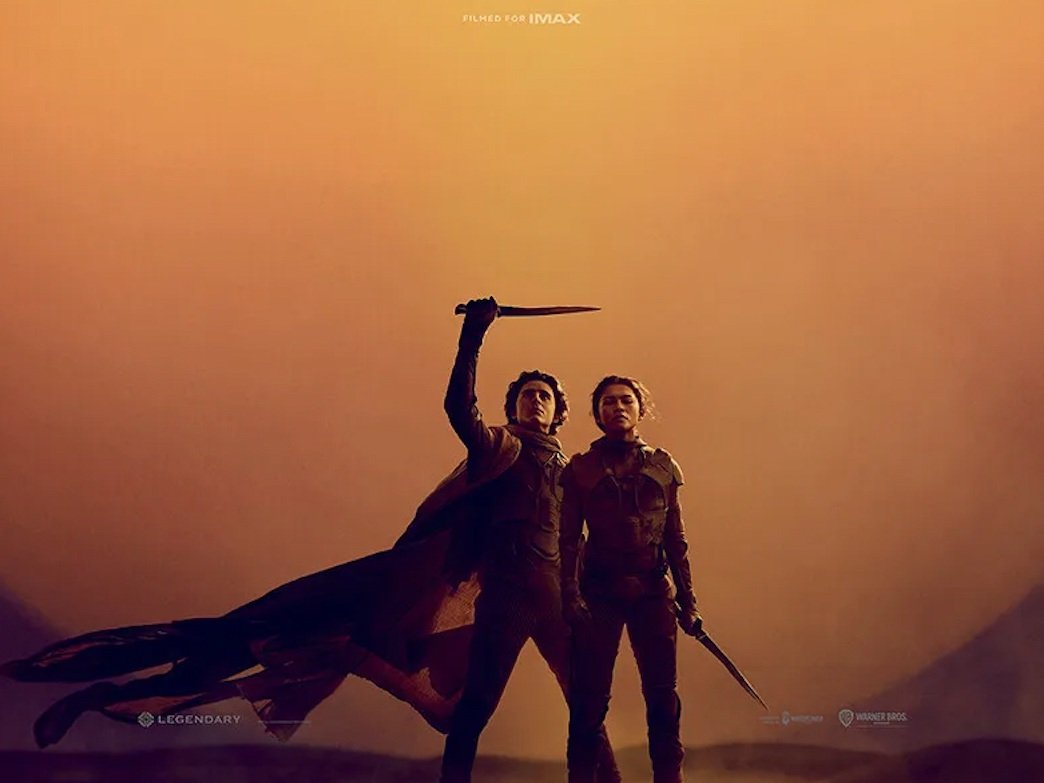

The soundtrack of the first film was, like the content, expositional of the world, characters, and themes of the overarching narrative, the fruition of each foreshadowed for the second. In Dune: Part Two, the musical elements established in the original are expanded and fulfilled. Some have critiqued the dramatic culmination of the film as not fully ‘living up’ to the original, but the same cannot be said of the score. New leitmotifs are masterfully interwoven with adaptations and reproductions of themes in the first film, signifying plot movement and character development. The most prominent original piece of music accompanies the love scenes between Paul Atreides (Timothee Chalamet) and Chani (Zendaya) which recurs at various instances throughout the film, building and building towards its use in the emotionally climactic and grandiose finale where Zimmer musters an excess of strings, percussion, and electric guitars to fashion the most epic version of the theme. It is an instant classic for Hans Zimmer: his characteristic synthesis of sentimental and rousing. It is a Zimmer score through and through, with some integral experimentalism scattered throughout.

I wholeheartedly recommend seeing Dune: Part Two on as big a screen as possible, not only for its visually stunning technical elements, but with surround sound audio to fully immerse yourself in Hans Zimmer’s latest cinematic masterpiece. It is currently showing evenings at the New Picture House.